I didn’t want to watch it at first. My partner had been telling me for weeks that I needed to see this show, and I kept finding reasons not to. I said I was tired. I said I wasn’t in the mood for something heavy. The truth was, I already suspected what it would ask of me.

Right before we pressed play, I finally asked him the question I’d been circling the whole time Is this going to make me mad? He didn’t hesitate. He just nodded and said, Yeah. Not apologetically. Almost like a warning. I laughed, but it wasn’t a real laugh. It was the kind you give right before you agree to walk into something you know is going to follow you long after it’s over.

The first season was exactly what I feared. It sat too close to When They See Us, too close to things I already knew too well. Not just as a viewer but as someone who had once sat in a jury box, staring at a sixteen-year-old Black boy whose life was being decided by a story that didn’t quite hold together.

He was being tried as an adult because a police officer was involved. Allegedly, the boy had slammed the officer to the ground, causing head injuries. But the evidence didn’t add up. There was video but it was grainy, incomplete.

A group of boys passing the camera. A police car following. Then the footage cut out, abruptly, almost surgically. When it resumed, the boy was running back into frame. The moment everyone needed to see, the moment the charge depended on was missing. The officer was much larger than the boy. It was an icy winter night. The officer admitted his recollection of the events were unclear, due to the head trauma. It wasn’t hard to imagine him chasing and slipping. Even the judge eventually confirmed what many of us as jurors already felt: the case was thin. But none of that mattered.

The boy took a plea deal. Watching him choose certainty over truth, punishment over risk, broke something open in me. I saw the system do what it does best, not prove guilt, but make innocence too expensive to defend. So when I say the first season of the show was heavy, I mean it carried the weight of memory. I came out of it not entertained, not enlightened but guarded. And that’s why, when my boyfriend was ready to start the second season, I dragged my feet. And why his frustration with me felt unfair and completely understandable at the same time.

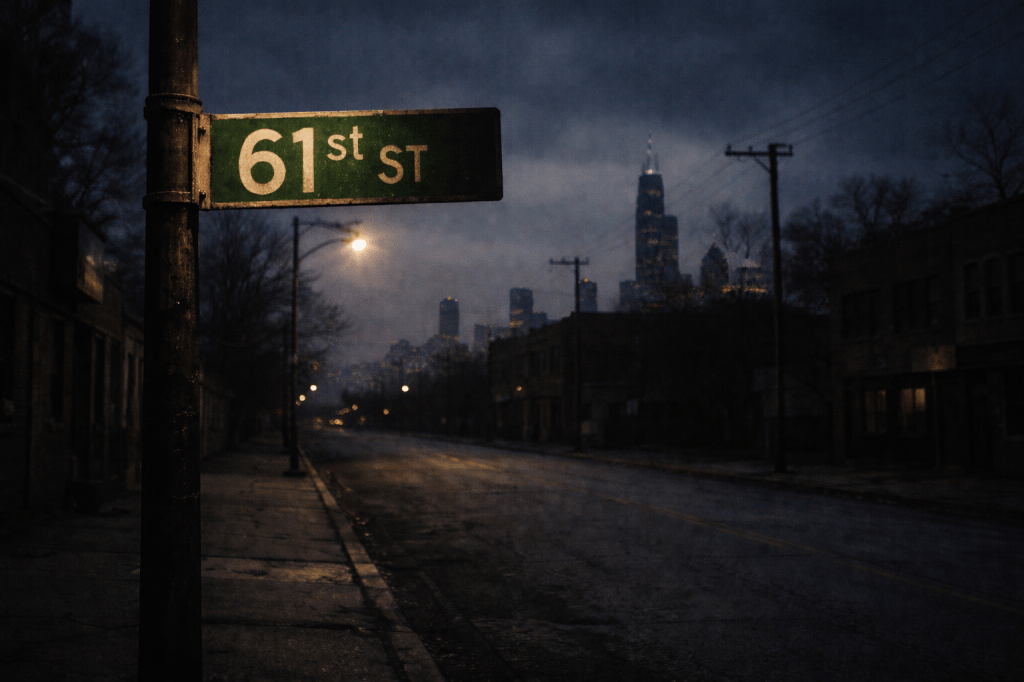

It was 61st Street, the legal drama he’d been insisting I watch, the one I kept putting off. When I finally allowed myself into the second season, I was surprised by what angered me most. It wasn’t the system this time, I expected that. It was the wife of the protagonist attorney Franklin Roberts, Martha Roberts portrayed by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor. Her refusal to stand by him. Her inability to see the long game.

She judged him not by his character or his consistency, but by her fear. And that fear hardened into certainty before he was given the chance to finish what he had started. There was nothing in his behavior that suggested malice. What he did withhold mattered, but it wasn’t betrayal. He kept his cancer diagnosis to himself. He didn’t immediately share the visit from Officer Logan who showed up uninvited. Those silences felt less like deception and more like an attempt to carry the weight alone as black men are often known to do.

But when fear is already present, unfinished truth can sound like a warning. To her, judgment arrived before belief had a chance. Belief in a vision that required time. But belief, for her, was dangerous.

The more I sat with it, the more I understood why. Black women have carried us for generations. They have been strong because they’ve had no other choice. They have not been afforded the luxury of faith, they’ve been trained in survival.

Fear, for many of them, isn’t a weakness; it’s an inheritance. A necessary one. Black women have always known the cost of trusting systems that don’t protect them, and sometimes that caution spills over onto the men they love.

They are among the most vulnerable in this country and yet have been asked again and again to be its backbone, its conscience, its saviors. That strength, though, often comes at the expense of belief. Not because Black women don’t love Black men, but because they’ve been forced to raise boys into men who must survive a world that has rarely proven itself trustworthy.

61st Street exposes that tension clearly: the burden of raising men who can be believed in, while having every historical reason to doubt what belief might cost.

Watching Martha ask Franklin to leave stirred something older in me something I didn’t expect. It reminded me of my own mother.

She was loving. Supportive. Present in all the ways that mattered and in many ways, still is. But there were moments growing up when I needed her most, and she went quiet. Not physically absent. Emotionally unavailable. As if whatever I was carrying felt too dangerous to sit with.

I don’t think she didn’t care. I think she didn’t know how to hold what I was becoming. I think fear stepped in where language failed.

Watching Martha struggle to understand Franklin’s long game, I recognized that same pattern. Not rejection, but retreat. Not cruelty, but confusion. When belief feels risky, distance can feel like protection.

As a child, I didn’t have the words for that. I only knew what it felt like to be overlooked when deep down I needed understanding, attunement.

As an adult, I see it differently. I see how Black women are asked to carry so much that sometimes the safest option feels like stepping back. But I also know what it costs Black boys when the people they trust most can’t stay present through their becoming.

I want to be careful here, because this isn’t a condemnation. Black women have been asked to be strong long before they were allowed to be soft. They have been the steady ones, the ones who stay, the ones who make a way out of no way. That strength has kept families alive, kept communities moving, kept men like me breathing long enough to become ourselves. I don’t write this unaware of that debt. I write this because I honor it.

And still, I need to ask something difficult. What happens to Black men when belief is always delayed until certainty arrives? When love shows up as caution but not as faith? I understand why fear feels safer than hope. I understand why protection sometimes looks like distance. But I also know what it costs Black boys when belief is withheld just long enough for them to doubt themselves.

I’m not asking Black women to abandon their instincts or ignore their history. I’m asking for room. Room to try, room to fail forward, room to be believed in before the proof arrives. Not blind trust. Shared risk. The kind that doesn’t ask anyone to carry the weight alone.

Leave a comment